The Story of the Discovery of Neurons

The story of how two opposing scientists discovered neurons

In 1665 Robert Hooke discovered cells in dead plant tissue and developments in the 1700-1800s by many biologists including Theodore Schwann and Jan Purkinje had shown that the tissues of animals are composed of cells. Yet, the brain remained a mystery.

Hooke's drawing of cork in his landmark publication, Micrographia (1665)

The methods of preparing samples and the limitations of light microscopes meant scientists were unable to see through the dense network of brain tissue leading many to begin to believe that the brain and nervous tissue was an exception to cell theory and composed of a different type of matter.

Golgi and the Black Reaction

A breakthrough occurred in 1873 when Italian pathologist, Camillo Golgi developed a method known as the Black Reaction to see past the dense network of tissue. Using potassium dichromate to harden brain tissue and adding silver nitrate, he was able to stain the brain cells, identifying the main body of the cell. Yet, Golgi’s method was limited as the fine branches that emanated from each neuron were faint with no obvious connection to the neighbouring cell.

Golgi proposed that each neuron’s branches joined to form one large connected network of cells throughout the body supporting a theory known as Reticular Theory

Golgi's first diagram of neurons using his staining method. Vertical section of the olfactory bulb of a dog (1875)

Santiago Ramon J Caja

Cajal self portrait in his laboratory

14 years later, Santiago Ramon J Cajal, having been persuaded by his anatomist professor father to abandon a career as an artist to study medicine, discovered Golgi's work.

Improving Golgi’s method Cajal was able to stain individual neurons. Having stained the cells he produced dozens of intricate drawings showing the cell body and dendrites of individual neurons.

Finding no journal willing to publish his work he founded his own and in 1888 printed 60 copies of his work Revista Trimestral de Histología Normal y Patológica. Posting the copies to anatomists across the globe he outlined his theory that nervous tissue is not continuous but is made of discrete cells that are not connected to each other.

Cajal's drawings of Purkinje cells

Cajal's drawings of Purkinje cells

The 1906 Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology

Cajal and Golgi were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1906 for their discoveries yet they continued to disagree throughout their lives on their opposing theories with Cajal commenting that “[it is] a cruel irony of fate to pair, like Siamese twins united by the shoulders, scientific adversaries of such contrasting character!"

“And the winner is…"

In the 1950s studies of nervous tissue using the electron microscope confirmed Cajal’s theory; nervous tissue is made of discrete, independent neurons rather than one continuous network in what we now refer to as the Neuron Doctrine, a central tenet of modern neuroscience. The neurons transmit messages to neighbouring cells at junctions known as synapses

Typical central nervous system synapse (credit below)

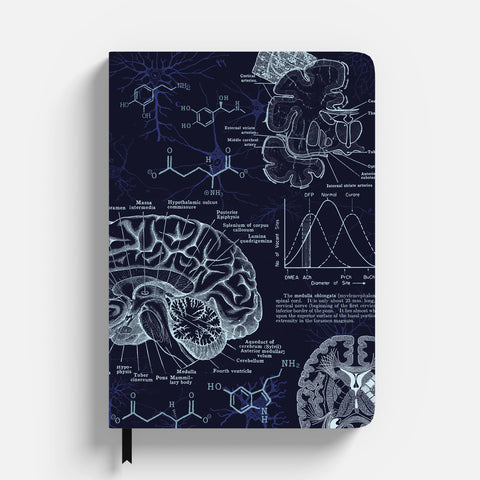

In recognition of the work by Cajal, we included several of his drawings on our Neuroscience Notebook cover.

Synapse image By Original: Curtis Neveu Vector: Pixelsquid - Own work based on: Neuron synapse.png by Curtis Neveu, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97072194)

Leave a comment